Beetlejuice Beetlejuice

36 years after Tim Burton's 1988 horror-comedy classic comes the long-awaited sequel, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice. Paying tribute to the original and its distinct, handcrafted visual style, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice seamlessly blends traditional filmmaking with modern VFX techniques.

Our team delivered invisible VFX, completing 253 shots that augmented the film's unique aesthetic and brought a Burtonesque cast of creatures to life. These included a creepy Baby Beetlejuice, a dismembered Delores, Charles Deetz bitten by a shark and CG snakes, all the while partially building and extending the iconic attic model. Working closely with Production VFX Supervisor, Angus Bickerton, puppeteers, costume designers, and other crafts, our team—led by VFX Supervisor Mat Krentz and VFX Producer Dan Booty—seamlessly integrated CG enhancements with practical elements and effects, preserving the film's throwback and handcrafted feel while using contemporary technology.

As ever, working with the team at Framestore was a delight from start to finish. Mat Krentz and Dan Booty led a magnificent team in Vancouver ensuring the highest quality throughout. They shone brightly with creativity and their enthusiasm never dimmed. They also provided peace of mind because you could be sure that their work would be nothing less than exemplary. Navigating a descent into the afterlife together was a joy. I’d invoke them anytime. Framestore Framestore Framestore!

Beetlejuice Beetlejuice | Showreel | Framestore

Creepy Baby Beetlejuice

Baby Beetlejuice’s prosthetics and models were created by the production-side art department. Framestore’s team was tasked with digitally augmenting their work to ensure seamless integration into the final scenes. Most of the work focused on digitally replacing the puppet’s hands and feet to enhance articulation and the character’s creepy movements. This involved developing a robust tracking system, meticulously painting out the puppeteers and, where necessary, augmenting the practical costume with CG to ensure a seamless final finish.

The team also enhanced Baby Beetlejuice's creepiness by adding subtle - and often gross - details, such as wetness to his eyes, spit, and CG flies buzzing around the character’s grubby face. Costume augmentations also contributed to the overall effect.

Most of our effort goes into creating supporting visual effects, primarily enhancing what the puppets can't achieve on their own. This work is not just about visual accuracy but also about boosting the puppet’s ability to express emotions and actions convincingly.

Dismembered Delores

Delores, portrayed by Monica Bellucci, is a soul-sucking demon intent on haunting Beetlejuice - her former beau. In her first appearance, her body parts emerge from different boxes, gather together, and are stapled to reconstitute her. Framestore’s team created each body part asset and managed the process of assembling them throughout the sequence.

The goal was to make the effect balanced to not be overly bloody or gory, in keeping with the movie's offbeat tone. To achieve this gruesome yet comical look, the team used aged, dry meat as a reference. Mat Krentz was on set for the sequence shooting, coordinating with multiple puppeteers to ensure the proper placement and combination of the body parts and the layers needed for the VFX team to assemble the final sequence.

“The mix of practical and digital effects in this scene was challenging,” explains Krentz. “We had to bodytrack each actor and render CG limbs with ‘meatcaps’ to blend with the live-action footage. Some parts, like the torso, were fully replaced with CG, requiring detailed cloth simulations for realistic movement. Our CG and paint teams did an amazing job preparing the CG assets and cleaning up parts of the frame where those pieces needed to go. CG Supervisor Hitesh Solanki played a key role in managing the complexities, ensuring the digital elements seamlessly integrated with the practical effects, maintaining the scene's surreal yet comical tone.”

Shark Bite Cavity

In this sequel, Charles Deetz is in the afterlife - having been bitten by a shark which left only half of the body behind, resulting in gouts of blood whenever he speaks. Framestore replaced the upper half of the body with a CG shark bite cavity, completing the costume design while adding animation control for the oesophagus that would drive the blood spurt effects. “We had a lot of fun collaborating on the comedic timing of the dialogue and spurts, especially deciding how much blood was just right without going overboard,” says Krentz.

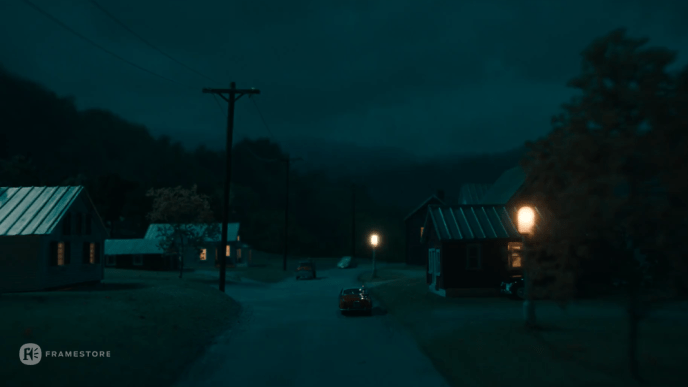

The Attic Model

The attic model is another example of how the team delivered seamless, invisible work by creating partial CG set extensions and replicating portions of the miniature town, flawlessly blending them with the handcrafted sets shot on location. "Everything had to look like it could have been captured in-camera,” says Krentz. “This meant it needed to be as imperfect and wonky as the surrounding sets. Not a single straight edge could be found, so integrating our work was quite the challenge!"

We're here to facilitate the director's vision and extend what's possible on set. Our goal is to make the CG elements undetectable. Tim Burton prefers effects that don’t scream CGI; they need to look organic, almost as if they’re not there.

Press

- Beetlejuice Beetlejuice: Mat Krentz – VFX Supervisor – The Art of VFX

- Framestore Crafts Some Ghostly and Ghastly VFX for ‘Beetlejuice Beetlejuice’ - Animation World Network

- ‘Beetlejuice Beetlejuice’ VFX Supe Angus Bickerton Details the Sequel’s Spooktacular Effects - Animation Magazine

- What’s Old Is New Again In The Madcap World Of Beetlejuice Beetlejuice - VFX Voice